If you were once a position player with a MLB team and find yourself in Triple-A, unless it's a rehab assignment, be afraid, be very afraid. The odds are high that you are not in your team's future plans. In theory, you are still competing at the highest level of Minor League baseball. But the fact that you didn't stick in your initial opportunity, means that you just went from hotshot to long shot.

When I read in the Sun-Sentinel blog last week that the Marlins had released Dallas McPherson, I was surprised. Despite his poor Grapefruit League play, the man hit 42 home runs at Triple-A Albuquerque last season. Let me repeat that, Dallas McPherson led the minor leagues in home runs last season and was looking for a job a week before the next season opened. This was not a Crash Davis-type accomplishment either, the guy is only 28 years old.

So it made me wonder what it means to excel at the Triple-A level? To the casual fan [me], MLB's minor league system represents a steadily increasing level of play, culminating at the Triple-A level. Back in 2003, the Marlins had two examples that indicated that something was amiss with the average fan's perception that the Triple-A level would house your best prospects, when Miguel Cabrera and Dontrelle Willis both made their jumps to the big leagues from Double-A.

This is a subject worthy of in-depth analysis, but anecdotal thoughts are the best I can do during tax season. To do so, I need to invoke a name which, in a perfect world, mere mortals such as myself should really not be allowed to bandy about in a public forum. But this is not a perfect world and so his name is Bill James.

If you followed baseball and weren't afraid of numbers in the early 80's, Bill James was a revelation. He ripped the job title of 'baseball analyst' away from ex-players with network and local broadcasting jobs. He did so by delving into statistics with imagination and wit. It was eye-opening and intoxicating to realize that many of the 'experts' weren't so much experts as they were cliche-machines. It was hard to seriously discuss baseball with anyone who hadn't read James. Here's what one well known economist and MLB fan, James Surowiecki, wrote in 2003:

Over the past 25 years, [Bill] James' work on player evaluation, player development, and baseball strategy—which inaugurated the body of baseball research known as sabermetrics, has revolutionized baseball analysis and overturned decades' worth of conventional wisdom.I remembered that James had written that minor league statistics do mean something, that they had a correlation to a player's eventual major league performance. I could not find that article to link. However, I did find an article by David Luciani in 1998 which discussed James initial article:

It has been more than fifteen years now since Bill James first wrote that minor league data meant something and it could be understood. James told us all that inevitably, major league baseball teams will eventually have to accept that. Surprisingly, major league GMs have paid too little attention to James’ philosophy and are suffering as a result of it.In Luciani's own analysis, he actually ascribed a percentage to predict various offensive categories going from minor to major leagues, i.e. 68% for home runs. Luciani summarized:

Quite simply, minor league statistics do mean something and perhaps the difficulty in accepting them has been because no one really knows how to read them. Even the so-called equivalencies that have become popular are useful but tend to over-reduce some columns and under-reduce others.But enough of the serious math, back to my anecdotal analysis.

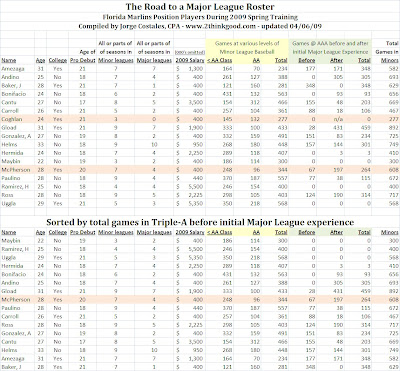

So is Double-A the new Triple-A? It reminds me of a kind of reverse Spinal Tap logic. [If you don't think the volume knob reaching 11 is funny, please leave the blog now - see video here]. So let's see how the current Marlins players [many who came up in other organizations] path to the big leagues have gone in terms of the number of games played at the various levels of Minor League baseball. While I do confine myself to players who were with the Marlins this Spring, only 4 of the 17 position players minor league careers were spent entirely with the Marlins, as such it is indicative of the mindset of various [18] organizations. The link to all the Marlins Minor League affiliates is here.

This is what I get from the numbers in my spreadsheet.

- An organization's best position player prospects are found in Double-A. That's where an organization houses what they believe to be their gems. Rehab aside, Triple-A is more of a spare parts factory.

- Where Chris Coghlan is reassigned to will reveal what they think of his prospects of being a MLB player. If it's Double-A he's still a hotshot, Triple-A he's now a long shot.

- A bigger appreciation of the kind of odds John Baker has overcome to earn a starting catcher's position in MLB after over 348 games in Triple-A without having reached a MLB roster.

- Even young stars pay their dues in the minor leagues. Hanley Ramirez spent four seasons in five cities affiliated with the Red Sox organization; Ft Myers [for loyal blog readers, this can not be used as one of our miracles] Lowell MA, Augusta GA and Portland ME. But not [of course] Pawtucket, RI--their Triple-A affiliate.

- Players--like Dan Uggla--who never return to the minor leagues after getting their initial opportunity, are rare.

- Partial guess, but the players with the most games at the Triple-A level probably constitute the next generation of coaches in professional baseball. These people have learned their craft, talent being a factor outside their control.

- Players learn that baseball is a business long before they appear on the radar of us fans. A player is much more likely to have been traded and/or promoted based upon factors other than talent, i.e. arbitration timetables, another prospect at same position and teams using up their allotted player movements [i.e. Andino].

I picture a Triple-A player reading his morning paper during the season and learning that a player from Double-A was just called up. A player with less experience and who is competing against inferior competition than he is, is getting his shot. At that moment, Triple-A guy knows something intuitively that Double-A guy can not possibly imagine. While there are exceptions, as a matter of pure odds, another player's dream just began to die.

Click on image to enlarge or print out

All articles referenced are copied in full at end of post.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------

Marlins show McPherson the door - Posted by Juan C. Rodriguez

The Marlins continued to pare down their roster after Tuesday night’s game, releasing infielder Dallas McPherson and reassigning outfielders Michael Ryan and Alejandro De Aza, and left-hander John Koronka to minor league camp.

McPherson spent all of last season at Triple-A Albuquerque and led the minor leagues with 42 home runs. He batted .239 (11 for 46) with three doubles, a homer, five walks and 15 strikeouts in Grapefruit League play.

With McPherson, De Aza and Ryan out of the out of the picture, the Marlins will not have a left-handed bat off the bench until the switch-hitting Alfredo Amezaga is ready to come back from a sprained knee.

The moves bode well for Brett Carroll, who is the only reserve outfielder remaining in camp.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Moneyball Redux

Slate talks to the man who revolutionized baseball.

By James Surowiecki

Posted Tuesday, June 10, 2003, at 1:15 PM ET

Although Michael Lewis' new book Moneyball is about Billy Beane and his successful transformation of the Oakland A's from also-rans to pennant contenders, the book's unsung hero is a man named Bill James. Over the past 25 years, James' work on player evaluation, player development, and baseball strategy—which inaugurated the body of baseball research known as sabermetrics—has revolutionized baseball analysis and overturned decades' worth of conventional wisdom. For most of his career, though, James was the archetypical prophet in the wilderness. He had a dedicated following of readers—many of whom went on to do groundbreaking statistical work of their own. But baseball owners and general managers essentially ignored him. In the past five years, though, all this has changed. The success of the A's, thanks in no small part to Billy Beane's clever application of sabermetric insights, brought James new attention, and this year a major league team (the Boston Red Sox) hired him as a senior adviser. For the first time in his life, Bill James is no longer a baseball outsider. So, to accompany last week's Book Club about Moneyball, I asked James to talk about Lewis' book, the future of baseball analysis, and some sabermetric puzzles.

******

To begin with the obvious question, what did you think of Moneyball? More specifically, what did you think of the book's account of your own work and of sabermetrics in general?

I tried to skip over the parts about myself. I established a policy many years ago of trying not to read anything written about myself. Mr. Lewis was very kind to me, and I appreciate his kind words, but ... it is unhealthy to base one's self-image on what other people say about you, even if they are generous.

For a lot of people, Moneyball will be the first sustained discussion of sabermetric analysis they've read. Given that, what do you think are the most important ideas—about player evaluation, player development, and team strategy—to take away from the book?

Well, of course, the ideas that made the greatest impression on me are the ones that aren't mine. The stuff in there about how an offense actually works, the relative value of little ball to power baseball ... I hardly saw that stuff as I read through it, because I knew that 20 years ago. What made an impression on me was, for example, the notion that some teams were paying a lot of money for unique packages of skills, when they could easily replace each of the individual skills by looking for different packages, different combinations of skills. The "front office view" of sabermetrics was extremely interesting to me, because I am trying to step up to the challenge of actually participating in a major league organization.

Reliably projecting a player's future is central to the success of any organization that can't—or doesn't want to—pay market rates for already established players. What are the most important attributes to look at in projecting a player's future? Is the future of a young hitter more predictable than the future of a young pitcher?

Yes, hitters are far more predictable than pitchers. Putting it backwards, because backwards is how you could measure it, the "unpredictability" of a pitcher's career is 200 percent to 300 percent greater than the unpredictability of a hitter's career.

In projecting a pitcher, by far the largest consideration is his health. There are a hundred pitchers in the minor leagues today who are going to be superstars if they don't hurt their arms. The problem is, 98 of them are going to hurt their arms. At least 98 of them. Pitchers are unpredictable because it is very difficult to know who is going to get hurt and when they are going to get hurt.

One of your most important insights is the idea that minor league batting statistics predict major league batting performance as reliably as major league statistics do. There have been certain players—think of 1980s players like Mike Stenhouse, Doug Frobel, Brad Komminsk—who seemed as though they would be terrific hitters but never really made it in the big leagues. Did they not get enough of a shot? Are they outliers? Or is there such a thing as a Four A (too good for Triple A, not good enough for the majors) hitter?

Well, no, there is no such thing as a Four A hitter. That idea, as I understand it, envisions a "gap" between the majors and Triple A, with some players who fall into the gap. There is no such gap. In fact, there is a very significant overlap between the major leagues and Triple A. Many of the players in Triple A are better than many of the players in the majors.

The three examples you cite are three very different cases. Stenhouse never had 180 at bats in a major league season, so one would be hard pressed to argue that he got a full trial.

Frobel is a different [instance], in which I think there probably wasn't a real strong case that he was a good hitter to begin with. Frobel hit .251 at Buffalo in '81, hit .261 at Portland—Pacific Coast League—in 1982. We would expect, based on those seasons, that he would hit .200, .210 in the major leagues, with a pretty ghastly strikeout/walk ratio—which is what he did. Then he had the one good year at Hawaii in 1983, looked like a better hitter, and fooled some of us into thinking that he was better than he was. But ... it was one year, 378 at bats, of performance that isn't that impressive. It wasn't enough, in retrospect, to conclude that he was actually a good hitter.

[Then] there are some players whose level of skill changes—drops—between two adjacent seasons or between two seasons separated by two or three years, usually because of an injury but sometimes because of some other factor. Frank Thomas is not the same hitter now that he was a few years ago; Tino Martinez isn't; Mo Vaughn isn't.

When those "disconnects" happen between major league seasons, we ascribe them to sensible causes—aging, injury, conditioning, motivation, luck, etc. Comparing major league seasons to minor league seasons, occasionally you get the same disconnect. Sometimes a guy simply loses it before he establishes himself in the major leagues. That's what happened to Komminsk, I think—he shot his cannons in the minor leagues.

I'm trying to make two general points here. Point 1: When there is a disconnect between a player's major league and minor league records, some people want to ascribe this to some mystical difference between major league baseball and minor league baseball. Unless you can say specifically what that difference is, this is akin to magical thinking—asserting that there is some magical "major league ability," which is distinct from the ability to play baseball. The same sorts of disconnects happen routinely in the middle of major league careers—not often as a percentage, but they happen. Everybody who plays rotisserie baseball knows that some guys you paid big money for because they were good last year will stink this year. It is not necessary or helpful to create some magical "major league ability" to explain those occasional disconnects between major league and minor league seasons.

Second point ... the creation of new knowledge or new understanding does not make the people who possess that new knowledge invulnerable to old failings. I can't predict reliably who is going to be successful in the major leagues in 2004, even if we stick with the field of players who have been in the major leagues since 2000. I can't do that, because there are limits to my knowledge, and there are flaws in my implementation of what I know. The principle that minor league hitting stats predict major league hitting stats as well as major league hitting stats predict major league hitting stats can be perfectly true—and yet still not enable me or you to reliably predict who will be successful in the major leagues in 2004, because I still have limits to my knowledge and flaws in the way I try to implement that knowledge.

Within the sabermetric community, a pitcher's strikeouts-per-nine-innings ratio has traditionally been taken as a good indicator of his overall performance. The A's starters in the last two years—and especially this year—have relatively mediocre strikeout rates but have done a very good job of keeping opponents from scoring runs. Is there anything surprising in this?

The question embodies four assumptions that I would be reluctant to sign on to. First, it assumes that statistics from a third of a season are meaningful. Second, it assumes that what is true of the individual pitcher must be true of the team. Third, the special importance that we attach to strikeouts has to do with projecting a pitcher into the future, not with evaluating the present. As to evaluating the present season ... the strikeouts are no more important than the walks, probably less. Fourth, the A's strikeout-to-walk ratio is better than the league average.

Right now, there are at least three teams—the Red Sox, the Blue Jays, and the A's—who appear to be employing a sabermetric methodology with some rigor. Even with more outlets for experimentation, are there still ideas you've proposed (either in terms of player evaluation or game strategy or organizational structure) that are still too radical for teams to consider?

Oh, certainly. Well ... it depends on what you mean by "proposed." I follow the maxim that you never start an argument you can't win. If an idea has no chance of gathering a following, I might sit on it rather than throwing it out to drown.

There's a general perception in baseball that players are now aging differently and continuing to perform better for longer (players like Randy Johnson and Roger Clemens and Barry Bonds being obvious examples). Do you think this is actually true, or is it simply a matter of a few extraordinary outliers?

It's just outliers. Randy Johnson and Clemens and Bonds are not only the obvious examples; they are the whole basis of the argument. Clemens and Johnson were born in 1962, 1963, and are still pitching well, and this focuses attention on them. But if you make a complete list of pitchers born in 1962 and 1963, their value peaked in 1990 and has declined by more than 80 percent. Other pitchers of the same age include Mark Gubicza, Doug Drabek, Jeff Montgomery, Randy Myers, Sid Fernandez, Danny Jackson, Chris Bosio, Mark Portugal, Jeff Brantley, Eric Plunk, Bill Wegman, Bobby Thigpen, Jose Guzman, Scott Bankhead, Greg Harris, Les Lancaster, Greg Cadaret, Todd Frohwirth, Jay Tibbs, John Dopson, Jeff Ballard, Charlie Kerfeld, Urbano Lugo, and Calvin Schiraldi. Have you seen Chris Bosio lately? He's a pitching coach somewhere. ... Looks like he's about 63.

It seems as if one of the places where teams might be able to carve out a competitive advantage for themselves is in the area of keeping pitchers healthy. The A's seem to think they've figured out how to do this. Do you think they have? If so—or if you think it's possible to adopt a program that would keep pitchers healthy—what would the key components of that program be?

It is an area infinitely capable of research, learning, and improvement. So if you're asking, "Are the A's at the finish line?" the answer is "Nowhere near." If you are asking if the A's are ahead of the rest of us, the answer is "Apparently they are."

To generalize wildly, defense has always seemed like the most difficult skill to capture statistically. Your Win Shares method seems to do a good job of describing players' defensive performance. But what do you think of the prospects of using play-by-play analysis to differentiate players' defensive skills? Is it possible to draw a meaningful separation between data and noise at the play-by-play level?

Yes, it is possible. But ... this is among my primary projects right now, and I don't want to talk about the sauce while it's still in the skillet.

What's the next frontier of baseball analysis that will be explored? What's the next frontier that should be explored?

Whether it is the next great frontier, who the hell knows, but one area that is open is the area of league decision-making—trying to think logically and clearly about how leagues should behave. Teams try to behave logically; players try to behave logically. Leagues, because they are formed of competing interest groups, often fail to address issues clearly, and thus arrive at illogical positions from the failure to address issues proactively. Simple example: It would have been far better for [professional] baseball to have provided bats for the players. At the start of each game, the umpire brings out 24 bats to be used by the two teams; these bats are the only bats which can be used in the game. There are several reasons why this is better, from the league's standpoint, than allowing the sporting goods companies to become pro bono suppliers of bats. But they didn't do it, simply because nobody was thinking about the issue from the standpoint of the league.

In the 1984 Baseball Abstract, you wrote: "When I started writing I thought if I proved X was a stupid thing to do that people would stop doing X. I was wrong." Twenty years later, at least a few teams have stopped doing X—and, just as important, started doing Y—because of your work, and the Red Sox are now paying you to tell them what they should be doing. Why did it take so long? How does it feel?

How does it feel ... good, but our vocabulary to describe feelings is limited. The other thing—I wouldn't write that anymore and can't really relate to it. The world is a cacophony of competing explanations. It takes time for people to focus on what you are saying, to sort it out of the thousands of other explanations. It was a part of the naive arrogance of youth to suppose that the world would react quickly to things that I learned, as if I were a doctor tapping the knees of the baseball universe. At 53, I am astonished at how much people react to what I write, rather than how little.

Did you learn anything about baseball from Moneyball?

Yes; I didn't have a real good idea of some of the things the A's were doing until I read the book. Actually—shouldn't admit this, I guess, but ... I had been working for several years on a book about baseball history, and thus, for several years, had not paid an awful lot of attention to what was happening in our own time.

I didn't, until reading the book, have any sense of who Billy Beane was, who J. P. Ricciardi was, or how they had been able to sustain the A's organization through difficult times. Some of those things I didn't know because I hadn't really been paying attention, and some of them I didn't know because, until the book came out, they hadn't been reported.

Finally, do you think most baseball teams will eventually adapt, and incorporate sabermetrics into the way they work on a day-to-day basis? Or will there always be a Pope to the sabermetrician's Galileo?

There will always be people who are ahead of the curve, and people who are behind the curve. But knowledge moves the curve.

James Surowiecki writes the financial column at The New Yorker.

Article URL: http://www.slate.com/id/2084193/

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------

What Minor League Stats Really Mean

by David Luciani

Published April 11, 1998

It has been more than fifteen years now since Bill James first wrote that minor league data meant something and it could be understood. James told us all that inevitably, major league baseball teams will eventually have to accept that. Surprisingly, major league GMs have paid too little attention to James’ philosophy and are suffering as a result of it.

Quite simply, minor league statistics do mean something and perhaps the difficulty in accepting them has been because no one really knows how to read them. Even the so-called equivalencies that have become popular are useful but tend to over-reduce some columns and under-reduce others.

I thought that if minor league numbers do mean something (and they do), then it would follow that some categories would translate to major league ability more than others. Before looking for data, my hypothesis was that a batters’ home runs would drop but that stolen bases would drop less, except as a result of a likely drop in times on base. Walks, I thought would go down and strikeouts would go up. Intentional walks would virtually disappear, at least in a player’s first year or two.

In order to “solve” the problem, we took data on every player who appeared in the major leagues the past four seasons and compared what they did in the majors to what they did at any one of a number of minor league levels in the same season. What a player did at Triple-A a year before playing in the majors doesn’t tell us what we want to know. A player can improve or decline during that year. We wanted years in which the player played in both the minors and majors and played a significant part in both seasons.

We then adjusted data for the environment in which the player appeared. If a player played half of his major league games in Oakland and half of his minor league games in Edmonton, we needed an adjustment for that. For pitchers, we needed to look at the league itself. Was it a hitter’s league or a pitcher’s league?

We made adjustments for playing time so that a player who had 500 plate appearances at Triple-A but 100 plate appearances in the majors has the 500 plate appearances at Triple-A reduced accordingly to match the context. We also performed a probability analysis on it to determine whether we had enough significant data to draw a conclusion.

What we discovered was that for batters, anything as far as down as the most competitive Single-A leagues, such as the Florida State League, can include significant data. For pitchers, anything below Double-A did not have any consistency whatsoever in relation to major league performance. Excluding playing time, we then examined everything on a per plate appearance (for batters) or per batter faced basis (for pitchers). Here were the results for the Triple-A level, results we often use in making projections of recently-promoted minor league players:

AAA BATTERS (% TRANSLATION PER PLATE APPEARANCE)

AB H 2B 3B HR R RBI BB IB K SH SF SB CS

101% 83% 76% 53% 68% 80% 74% 89% 55% 125% 172% 88% 76% 79%

AAA PITCHERS (% TRANSLATION PER BATTER FACED)

G GS CG IP H R ER HR HB BB IB K W L SV

127% 76% 22% 91% 110% 134% 139% 157% 119% 125% 198% 75% 63% 111% 21%

Note how much more a batter is asked to bunt in the majors. The best Triple-A hitter is just another bench player in the majors and the frequency of sacrificing reflects that. The speed translates pretty well, essentially the same when you consider how less frequently the batter will be on base in the majors.

For pitchers, look at how little Triple-A saves mean. Your 25 save guy from Triple-A becomes a five save guy even if he faces the same number of batters in the majors.

Obviously, you can’t just translate statistics and assume that it tells you exactly how a player would have done in the majors. You need first-hand knowledge of the player and witnessing his talents in person is the ultimate test. However, this tool gives you an accurate forecasting tool that can be used at least as a starting point, in combination with first-hand knowledge, to achieve better results.

---------------------------------------------------------------------

3 comments:

You're right: how'd you have the time for all this on April 6? Anyway, this is fascinating and something I've never thought about, but it seems you have a valid argument. But be careful. Call a HASMAT team if you get any powdery mail from Sacramento, Buffalo, or Indianapolis.

Jorge,

You've done a good job articulating something a lot of us fans have known intuitively for a while: Triple A is where careers go to die.

My understanding is that that Triple A is full of mashers that can hit the ball a country mile but have some other defect in their game, like maybe their defense is terrible or they can't hit a curve ball, etc. As a result of all these heavy hitting guys (like McPherson) being in Triple A, organizations don't want to send their top pitching prospects there (to have their confidence crushed like a 550 ft. HR ball). The lack of good pitching at this level, combined with a glut of heavy hitters means that AAA stats are inflated (there are also some ballparks that are very hitter friendly in AAA).

You are right. Being in AAA is not a good thing. Most stars go from rookie league to A to AA and then to the bigs.

"Players--like Dan Uggla--who never return to the minor leagues after getting their initial opportunity, are rare."

Uggla is weird example...

As a Rule 5 pick, the Marlins didn't have the chance to send him to the minor leagues without first offering back to the team they swiped him from.

Post a Comment